Waging a Battle of Ballots at the Polls this Fall

Author: Eliza Galaher, North and Central Coast Education and Outreach Specialist

July 19, 2022

When providing fair housing trainings, I sometimes explore sex as a protected class by asking people to imagine a single woman, before 1974, applying for a mortgage and legally being denied simply because the lender might conclude she wouldn’t be able to maintain payments without the support of a husband. And then I sometimes mention that I am a single woman who bought my first house in 2016 and that I can’t fathom such a time when I could have been turned away from homeownership strictly due to my sex.

Of course, there have been times in other contexts that because of my sex, my sexual orientation, and my gender expression, I have been marginalized, treated as “other” or “less than.” But my experiences, especially as a white, privileged person, have been negligible compared to those of millions of other Americans who are continuously and systematically denied their rights to housing, public safety, education, health care, bodily autonomy, employment, and the vote.

With today’s powder keg of a political and judicial climate, it is all the more important to mobilize with our votes and continue the fight to protect against the erosion of rights that have been so hard-fought, earned, and conferred. Afterall, the November midterm elections are only a few months away.

Now, because I work in the field of fair housing, I am going to center my thoughts here mostly on the connection between voting rights and housing rights. They are close siblings, with the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965 and the Fair Housing Act passed in 1968. Both were driven by the fearless, tireless work of the civil rights movement of that time that was led by Black Americans. But while these Acts were meant to end discrimination, they remain relentlessly challenged, sometimes on their own, and sometimes in ripple effect with one another.

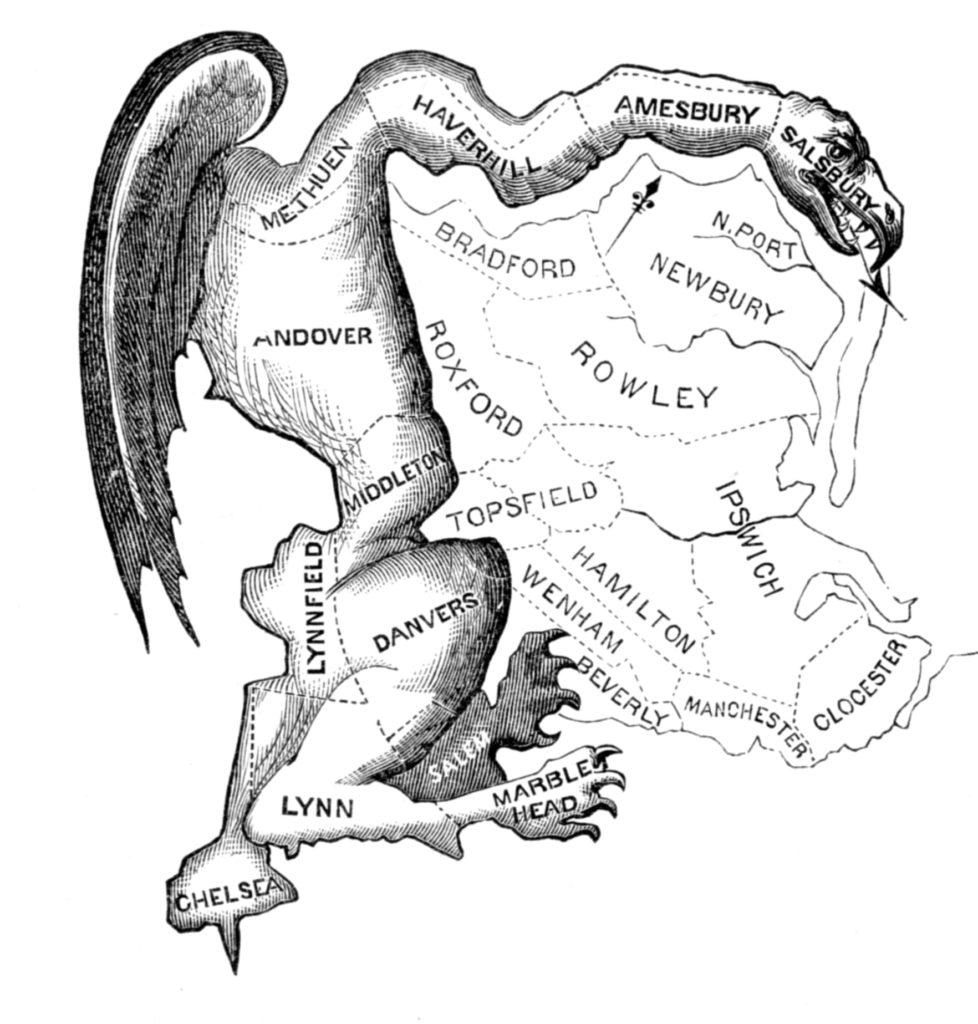

Take, for instance, the practice of gerrymandering. The term “gerrymandering” goes back to 1812, when Massachusetts governor Eldridge Gerry reshaped voting districts to his advantage in such a way that critics said they resembled a salamander:

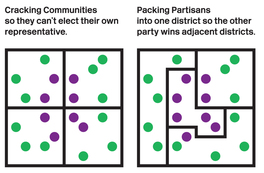

(A scary one, if you ask me.) Such self-interested political reshaping of districts disempowers voters by either packing them (constraining voting power) or cracking them (diminishing and diffusing voting power):

While reshaping districts is a legitimate and necessary process in and of itself after each 10-year census poll in order to account for growth in certain areas, gerrymandering is a direct corruption of that process. And despite Supreme Court decisions like 1995’s Miller v Johnson, which concluded that manipulative redistricting strategies “cannot be understood as anything other than an effort to segregate voters based on race,” subsequent Supreme Court decisions like 2013’s Shelby County v Holder have vastly weakened any means of holding accountable those in charge of redistricting.

So, gerrymandering—especially but not exclusively racially based gerrymandering—continues. And it does so with a debilitating impact on people’s right to have their votes count—votes for who represents and advocates for them; votes for city zoning issues; votes that ultimately influence the chances a person may have of acquiring and keeping housing that is fair, affordable, and inclusive.

In short, gerrymandering is a slippery, lizard-like cousin to redlining, creating spaces where people, their votes, and rightful access to opportunities promised to all Americans are disenfranchised. Unrepresented by politicians who would work to protect their needs and rights, people living in heavily gerrymandered districts cannot enjoy equal access to life, liberty, property, and equal protection of the laws, as is guaranteed under the 14th Amendment.

But gerrymandering is not the only means of pressing a thumb on the scale of voting rights. For instance, on Friday, July 8, 2022, Wisconsin’s Supreme Court outlawed the use of ballot drop boxes, which severely limits people’s options in that state to submit their votes at election time, including people who work, who have compromised immune systems, who have mobility issues, and people who have limited transportation.

In another potential blow to the democratic process, the United States Supreme Court has announced that this autumn it will hear a case known as Moore v Harper, which, according to this July 7, 2022, Guardian article, argues “the idea that state legislatures cannot be checked by state supreme courts when it comes to setting rules for federal elections, even if the legislature’s actions violate the state’s constitution.” Such a favoring of one branch of government over another negates the concept of checks and balances and puts still more power into the hands of the very politicians who gerrymander districts to their own advantage.

The clock of democracy is ticking. If the United States is to be a truly democratic country for, by, and of the people, it should be a house made of votes, not a house of cards, crumbling at the whim of a politicized Supreme Court or the folly of self-serving politicians. One central way to do that is for everyone—not just courageous, committed people like Shaye Moss and Ruby Freeman—but everyone to get out and vote this November.

If you have any doubt that your vote counts, please consider the rights you do have now, and the current trend toward eroding people’s rights. Encourage your friends and family to vote. Provide rides. Vote with the 14th amendment at the forefront of your mind. Be visible. Be bold. This is a battle of ballots.

Vote like our democracy depends on it—like there is truth and integrity in our country’s motto, “e pluribus unum.” Out of many, one. That’s how a safe, just, inclusive house is built.