Written by Marlee Baker, (they/them), Portland Metro & Salem Education and Outreach Specialist

September 15, 2023

“[The voice of justice] proclaims that fair housing for all – all human beings who live in this country – is now a part of the American way of life” – these were the words of President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968 as he signed the Fair Housing Act into law, federally prohibiting illegal housing discrimination based on Race, Color, National Origin, and Religion.

The history of fair housing law, as guided by that foundational vision of “fair housing for all,” has been marked by stages of evolution and expansion as we uncover discriminatory housing trends and barriers that disproportionately affect certain protected classes over time. Today, the protected classes under fair housing law have expanded to include Sex (defined to encompass Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity), Familial Status, and Disability. States and jurisdictions nationwide have also formalized additional protected classes dependent on local discrimination trends; for example, Oregon’s statewide protected classes include Marital Status, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, Survivor of Domestic Violence, and Source of Income. At the local level, we have also seen jurisdictions expand protected classes to include categories such as “Occupation,” “Age,” or “Citizenship.”

Today, a different barrier to equal housing access presents itself: discrimination based on housing status, or one’s experience of being unhoused. Discrimination against unhoused people is deeply ingrained into our societal psyche. Cognitive research shows that unhoused people elicit stronger reactions of contempt and disgust than any other stigmatized group in the U.S. This same research found that the part of our brains that registers when we are interacting with another human being is less likely to be triggered when perceiving an unhoused person – meaning unhoused people are literally dehumanized at the cognitive level.

The assumption that most individuals who are unhoused are severely mentally ill, addicted to substances, or have somehow become unhoused due to their own reckless choices is deeply misinformed. ACLU’s report, Outside the Law: The Legal War Against Unhoused People, describes how stereotypes perpetuate discrimination against unhoused people at both the interpersonal and systemic levels of policy. When people become unhoused, they are labeled by the housed majority as “homeless,” a derogatory term often used to frame unhoused people as dangerous and a blight to be concealed. This biased perception is then used to legitimize violent policies that target unhoused people, such as anti-loitering and anti-camping laws, all in the name of “promoting public safety.”

The primary factor shared between regions with high rates of homelessness isn’t poverty, mental illness, or substance use: it’s rental prices and vacancy rates. Regions with booming labor markets and low rates of unemployment actually experience the highest rates of homelessness. When we regard the effects of profit-driven housing development and NIMBYistic bureaucracy on the housing markets in these regions, we see how a foundational lack of affordable housing paired with skyrocketing rents exacerbates the risk of houselessness for those with individual vulnerabilities – suddenly one crisis, one late check, one car accident, one unexpected disability has the power to force an individual into homelessness.

Oregon’s current housing crisis can be understood within this framework. According to Street Roots, while rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Portland has risen 34% in the past year, available housing and transitional or emergent alternatives have shrunk. Oregon’s Regional Housing Needs Analysis found that the state currently lacks 140,000 units necessary to meet current population housing needs, and estimates that Oregon will need to generate about 580,000 more units over the next 20 years. As a result of this massive underproduction, Oregon now faces a housing affordability crisis: nearly half of all Oregonians spend at least 30% of their income on rent (placing them below the federal standard for affordability), and half of all evictions filed in Oregon between July 2021 and July 2022 were due to nonpayment. Since August 2022, that average has risen to about 80%.

Oregon used to have housing to accommodate diverse incomes, abilities, and needs; one such was single-room occupancies, or SROs. SROs were, most commonly, hotels whose rooms were converted into individual, long-term rental units with shared common spaces, like bathrooms and kitchens. People who were low-income, unemployed, elderly, living with disabilities, immigrants, recently incarcerated, or facing other housing barriers could afford occupancy in an SRO in an otherwise hostile housing market. However, due to urban renewal policies in the 1950s and 60s and deinstitutionalization policies in the 70s and 80s, SROs became essentially nonexistent, leaving vulnerable populations without housing, services, or support.

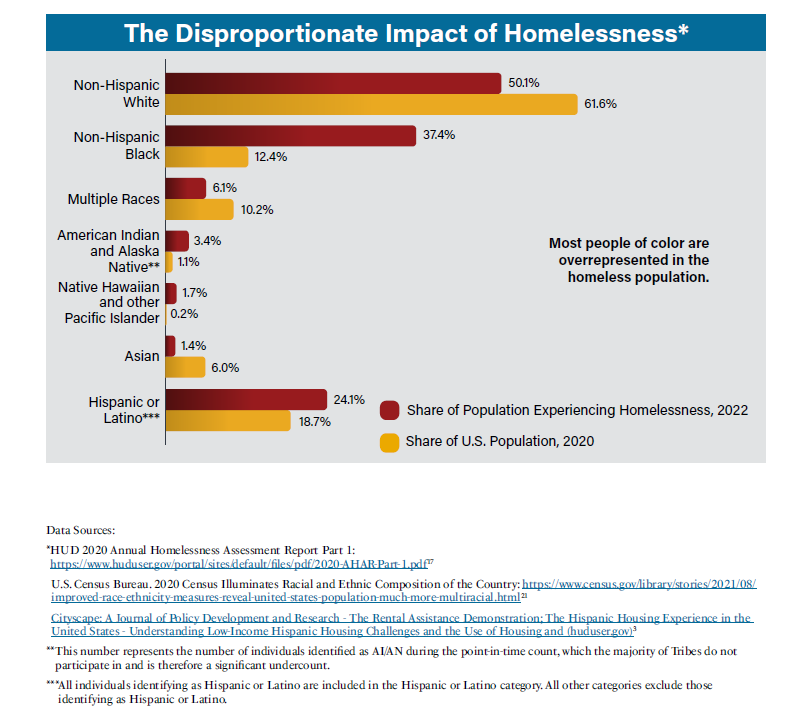

The effects of this housing crisis are inherently inequitable. Today, we see disparities within the unhoused population based on protected class and among those who are more likely to experience discrimination because they are unhoused. For example, Black adults are more likely to be specifically targeted for anti-homeless infractions, such as anti-loitering and anti-camping laws. This discrimination is compounded by the reality that Black people are also significantly overrepresented in the unhoused population, a disparity that is largely the result of long-standing systemic barriers that have historically limited housing opportunities for people based on race and caste. In addition to race and ethnicity, other populations that have experienced historical barriers to housing and who currently experience disproportionate rates of homelessness include people who identify as LGBTQIA+, and people living with disabilities.

So, if the housing crisis we see today is primarily the result of rapidly increasing rent and a lack of affordable housing development, then why does our society allow those who become unhoused to be vilified, dehumanized, and forced to bear the blame of a failing and inequitable system?

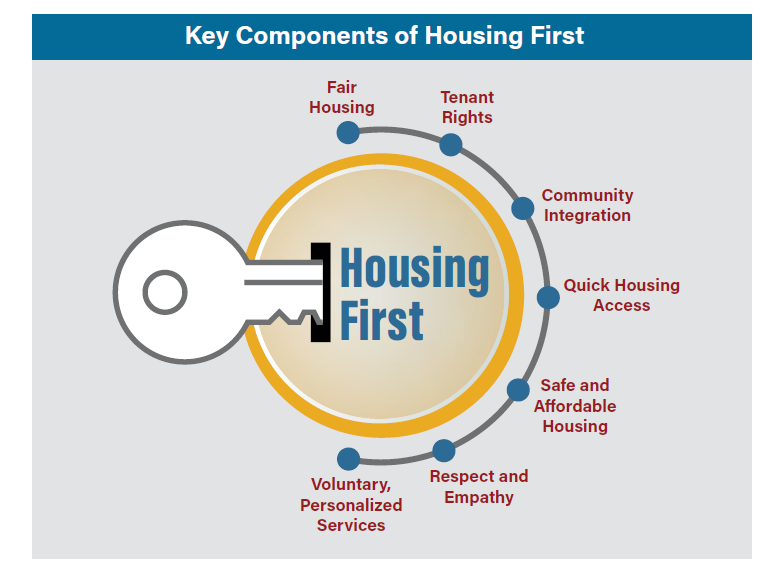

Given these intersections of discrimination, I believe that Fair Housing may have a renewed role in addressing housing status discrimination. While fair housing protections only extend to those living in dwellings, fair housing could help address disparate barriers to accessing housing. The Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness, published by the United States Interagency Council on Homeless (USICH) in 2022, specifically identifies fair housing as a key component in addressing the housing crisis.

The USICH centers the reality that “racial and other disparities” exist among people experiencing homelessness and that these same individuals also “have fewer opportunities to access safe, affordable housing and health care and face more barriers to fulfilling these basic needs once they lose them.” The plan goes on to outline how enforcement and education of fair housing can be used “combat other forms of housing discrimination that perpetuate disparities in homelessness” and thereby increase housing access.

Some jurisdictions across the United States have formalized local protections for unhoused people. In November 2022, Salem, Oregon, voted to add “housing status,” or an individual’s actual or perceived lack of permanent housing, as a protected class. According to Sec 97.070 of the Salem Municipal Code, it is now “unlawful for a person to discriminate against any individual in the selling, renting, or leasing real property, provision of public accommodations, or employment on the basis of housing status.” Acts of discrimination against unhoused individuals can be reported to the Salem Human Rights Commission and criminally punished. With this update, Salem joins a steadily growing list of other jurisdictions nationwide to add housing status as a protected class, including Madison, Wisconsin, Louisville, Kentucky, and Washington, D.C.

The City of Salem’s decision to formalize housing status as a protected class is the direct result of a survey conducted by Western Oregon University. Researchers found that nearly 95% of unhoused individuals in Salem reported experiencing daily discrimination, primarily based on housing status. Additionally, nearly every unhoused individual reported witnessing or hearing about discrimination occurring to someone they knew. While conducting outreach to social service providers throughout the City of Salem, I have listened to many advocates share stories about the discrimination and barriers their clients have faced due to housing status. Such anecdotes include:

- Housing providers who make discriminatory statements that dehumanize currently unhoused applicants, such as: “I don’t want those people living here;”

- Housing providers who, upon learning of an applicant’s housing status, begin asking questions about previous substance use, criminal history, or mental illness that aren’t asked to other applicants;

- Housing providers who share inconsistent or false information about the availability of units after learning about an applicant’s housing status;

- Housing providers who enforce policies more strictly and issue notices more frequently to residents who previously had impermanent housing.

Given the novelty of housing status as a protected class, Salem and jurisdictions nationwide are still determining how to legislate and formalize housing status protections and enforcement. Washington, D.C. demonstrated what such policies could look like when, in 2022, it passed the Eviction Record Sealing Authority and Fairness in Renting Amendment Act to decrease the top barriers to housing experienced by unhoused people, specifically poor credit scores and eviction records. Thanks to this bill, all eviction records will be sealed after three years, and landlords are now prohibited from denying applicants based solely on credit score, old or irrelevant rental history, or sealed evictions.

Under fair housing protections, the traditional barriers that often prevent unhoused people from regaining equal access to housing may be more easily navigated. Let’s assess the following example: A person who has been unhoused for several years is applying for an apartment. Where a housing provider might generally dismiss applicants with significant gaps in their rental history, under the protected class of housing status, this applicant may be able to explain their housing status, provide evidence of income, and request that the housing provider overlook this barrier.

The foundational premise of the Fair Housing Act is to protect populations from discrimination in housing transactions due to dimensions of their protected identity. When jurisdictions and states add housing status as a protected class, this decision affirms a fundamental shift in the way we, as a society, understand the importance and role of housing – not as a moral reward preserved for the “deserving” or those of certain identities, but as a universal right necessary for human safety, dignity, and flourishment. Housing status as a protected class asserts the reality that our current housing crisis is the result of inequitable policies that disparately impact historically marginalized and discriminated populations. Protections based on housing status will hold advocates, legislators, and systems accountable to a larger vision, to ask and actualize the future posed by Fair Housing: what would our society look like if everyone truly had equal access to housing?