Some people think of housing discrimination as something that occurred in the distant past. Housing discrimination was indeed more blatant in the past, but it is still a problem today.

In 1919, the Portland Realty Board added to its code of ethics a provision prohibiting members from selling property in white neighborhoods to people of color. In 1924, the National Association of Real Estate Board (NAREB) published its first code of ethics that stated, “A Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.” The code of ethics changed in 1956 to remove racial references, but the discriminatory intent behind the code remained.

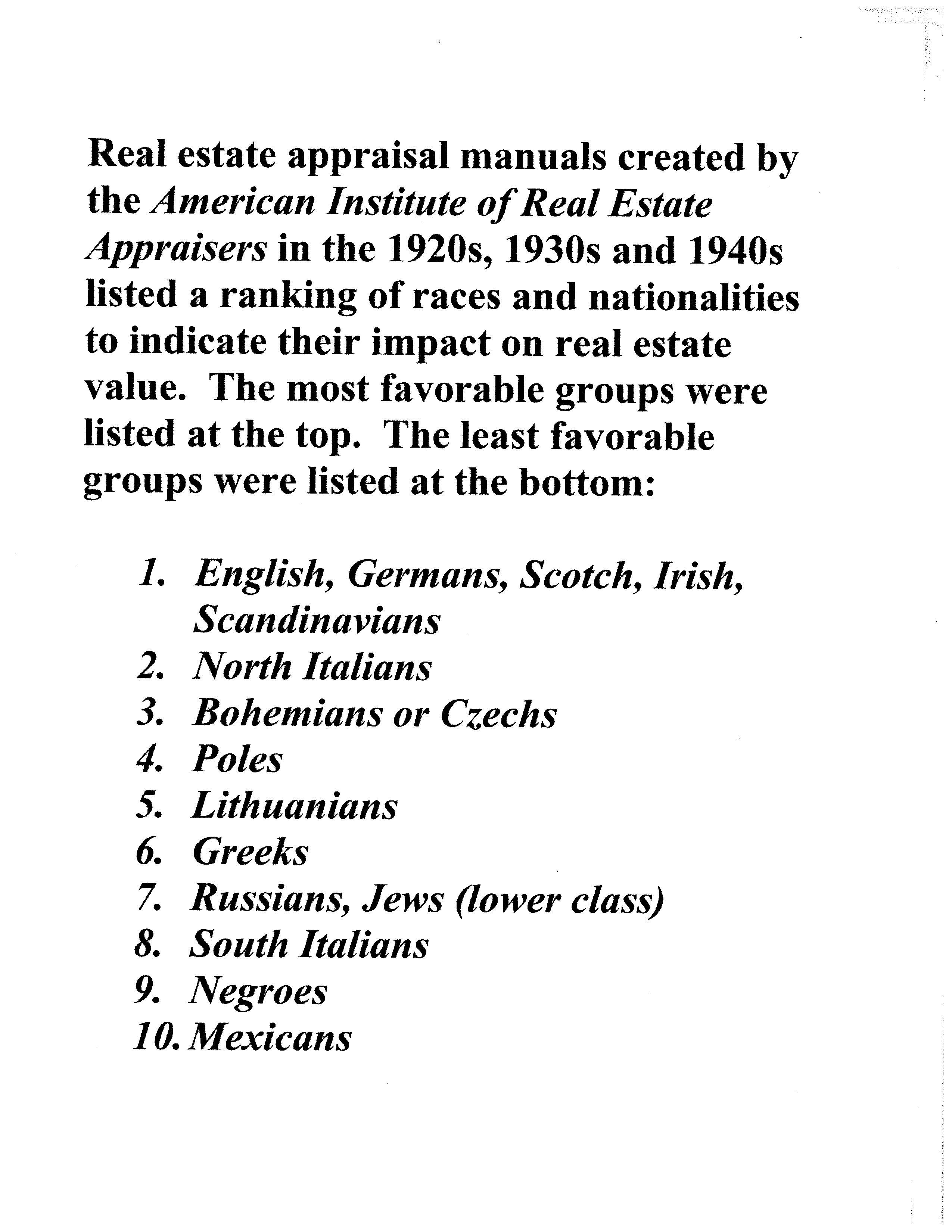

From the 1920s-40s, it was common for home appraisers, mortgage lenders, insurers, and others to assess the property values of neighborhoods based on the race and ethnicity of those who lived there. Those with lighter complexions were ranked more favorably than those with darker complexions, as is seen in the picture below. This led to people of color being denied home loans, charged higher insurance and interest rates, and having their property valued for less than it’s true worth. It also disproves the persistent myth that the integration of neighborhoods would “inherently” reduce home values. Any negative impact on home values instead came from the intentional actions of appraisers and realtors.

In 1957, Oregon passed fair housing legislation that prohibited property owners and their agents who received any public funding from discriminating “solely because of race, color, religion, or national origin,” in the sale, lease, or rental of any “dwelling place for a person or family…in a building containing five or more such apartments or units.” In 1959, the law was amended to also apply to any “person who, as a business enterprise, sells, leases or rents real property.” Realtors in Oregon could get their license revoked if they violated the new law, but the legislation did not provide for enforcement mechanisms, placing the burden of proving discrimination on the person who was discriminated against.

The national Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968 and made it illegal to discriminate in housing based on race, color, religion, and national origin. The act was amended in 1974 to include sex, which includes sexual harassment. In 1988, it was amended once again to include familial status (which means families with children under 18) and people with disabilities. The 1988 amendment also finally created enforcement mechanisms.

While the Fair Housing Act makes it illegal to discriminate based on race, many Black homeowners still face racial discrimination in housing today. The COVID-19 pandemic has given homeowners a unique opportunity to take advantage of low home-refinance rates and many people are getting their homes appraised – a process where the value of a home is determined. The New York Times shares stories of Black homeowners in Florida, Connecticut, and California who all had their homes appraised for less than their true value. Two of the homeowners resorted to their own testing. One woman, who was Black, left the house while her white husband met with the appraiser. Another gentleman had his white neighbor stand in for him during the appraisal. The results? In both cases, the appraisals came back significantly higher when the Black homeowners were not present. Homes in predominately Black neighborhoods tend to be valued lower than similar homes in predominately white neighborhoods, but even in mixed-race and majority white neighborhoods, Black homeowners’ homes are valued lower than their white neighbors.

Home seekers also face racial discrimination. Newsday conducted 86 fair housing tests over three years to determine the prevalence of discrimination in the Long Island real estate market. Out of the 86 tests conducted, 34 provided evidence of unequal treatment of testers based on race. Steering, or directing people to different neighborhoods based on their race, was widely used. This is a practice that is illegal under the Fair Housing Act. Agents often discussed school district ratings – coded language that implies the racial make-up of a community. Overall, Black testers experienced unequal treatment 49% of the time, compared to Hispanics (39%) and Asians (19%). Of the twelve largest real estate brands on Long Island, agents at only two of the firms did not engage in discriminatory behavior. When people are denied housing based on their race, people of all races are denied the benefits of living in an integrated community. We highly recommended reading the full Newsday article and watching the 40 minute documentary.