The history of racial discrimination and segregation in housing plays a significant role in the criminal justice and health disparities we see today. People of color have long faced both formal and informal mechanisms of segregation, the effects of which can be seen in police-community relations and health outcomes.

Historically, formal mechanisms of maintaining segregation included redlining, using restrictive covenants to put racial restrictions on who was eligible to buy a home, and appraisal lists that valued homes in white neighborhoods higher than those in non-white neighborhoods. Informal mechanisms included hate and harassment by neighbors and community members when people of color moved into white neighborhoods.

These systems of exclusion created the conditions – such as crowded, unsafe, unstable housing and areas of greater concentrated poverty – that have put Black, indigenous and other communities of color at greater risk and consequently resulted in the inequalities we are seeing today.

Police-Community Relations

We know that police violence against Black communities – and specifically the killing of unarmed Black men, women, and children at the hands of police – has been occurring for hundreds of years.

Historic redlining and the resulting and ongoing racial segregation in so many places across the country is among the underlying causes of the police violence against Black communities. In May, Time magazine drew similar parallels to Minneapolis’ history of racial segregation and the role it played in the killing of George Floyd.

A 2018 study by the Boston University School of Public Health was among the first to study this close relationship between racial segregation and police killings of Black men, women and children. The study found states with a greater degree of structural racism, particularly residential segregation, have higher racial disparities in fatal police shootings of unarmed victims. From the article: “for every 10 point increase in the state racial segregation index, there was a 67 percent increase in the state’s ratio of police shootings of unarmed Black victims to unarmed White victims.”

COVID-19 and health disparities

Another continuing legacy of redlining and systemic racism has been disparities in health outcomes. We know that where you live can determine your health outcomes, including how long you might live. Black, indigenous, and other communities of color are also being disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

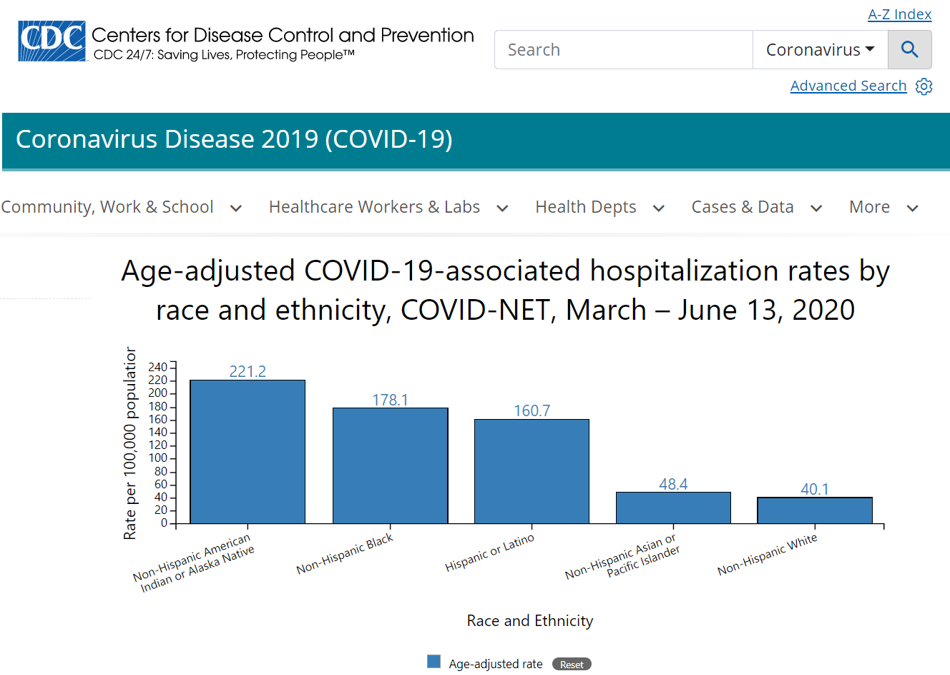

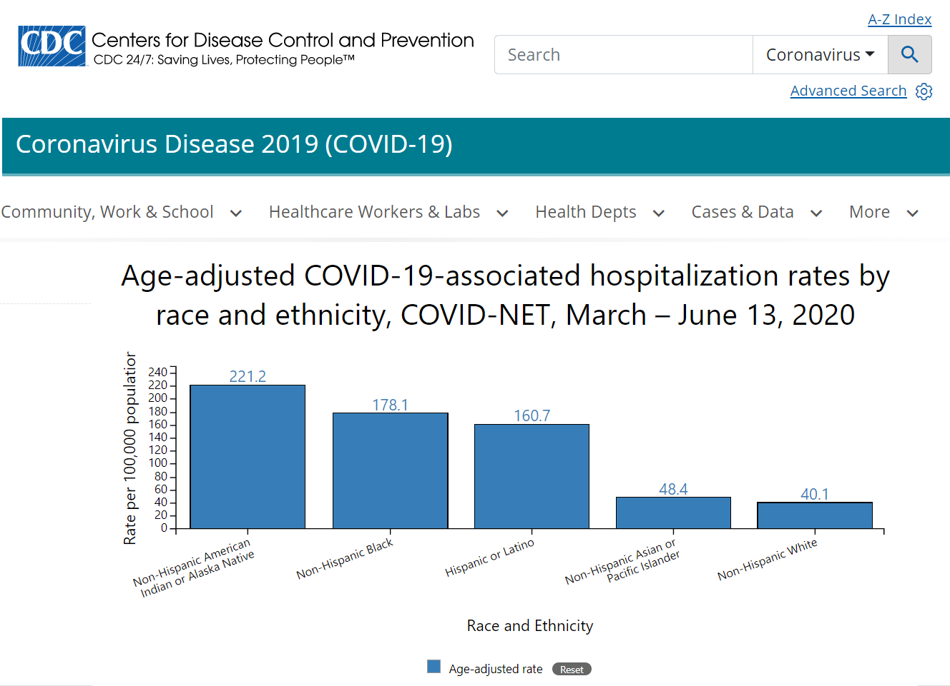

The Centers for Disease Control statistics show that, nationally, Blacks make up 21.2% of fatalities, despite being just 12.3% of the total population, and this CDC graphic illustrates the disproportionate rate of hospitalizations among Black, indigenous, and other communities of color.

In Oregon, Latinx and Hispanic communities have seen the highest rate of impact from COVID-19. According to Metro, in early May Latinx accounted for 27% of Oregonians with coronavirus whose ethnicity was known, even though the community represents only 13% of the state’s total population. The number of coronavirus cases is disproportionately high for Latinx communities, even as advocates have warned that Latinx populations may be fearful of reporting symptoms or being tested over concerns about legal punishment.

What we can do about these ongoing injustices?

First, we must recognize that communities of color have long known that racism is a public health pandemic. There is hope, however, as power structures, particularly historically white, male dominated power structures, are willing to recognize that to affect change, we must take action at the institutional level.

What can we do at an individual level?

- Examine history to understand the roots of discrimination and disparities

- Challenge and change long-held racist narratives

- Engage in and change the power structure: representation matters

Dr. Ibram X. Kendi also gives us guidance on what to focus on now:

- understand racism as the structure,

- then we can think about all the elements that make up that structure, such as all the policies that lead to Black people being disproportionately homeless

- then when you can focus on the inequities, then you can look at the policies (creating those inequities)

- then you can see the policymakers supporting seeking to transform those policies or (conversely) the ones resisting that

- then you can clearly see what the problem is and see who the problem is and can put focus on that what and on that who

- everyone of us has a job to do in this larger anti-racist struggle; each of us can fight against this in our community or our area of expertise; that’s what we can focus on.