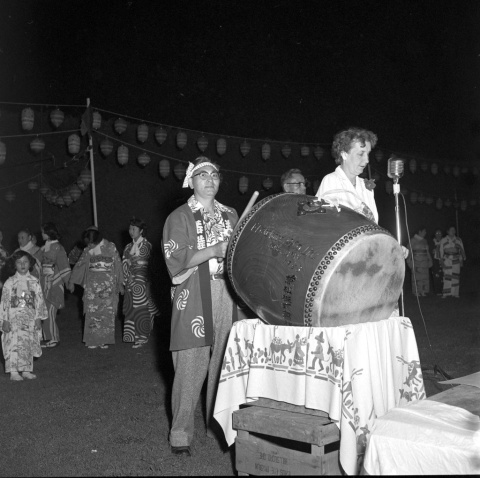

Portland Mayor Dorothy McCullough Lee speaking at Obon. Playing the taiko drum is Henry Matsunaga, ca. 1948-1954. Obon is an annual event hosted by the Oregon Buddhist Church (now known as Oregon Buddhist Temple) and attended by the wider Nikkei community. “Obon Festival- Mayoral speech” (ddr-one-1-254), Densho, the Mitsuoka Family Collection. (Source: Japanese American Museum of Oregon/ Densho Digital Repository.)

May is Asian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, designated to honor and pay tribute to the generations of Asian and Pacific Islander people who have enriched America’s history and are instrumental in its future success. This blog post highlights the histories and contributions of the different communities and myriad cultural experiences of Asian and Pacific Islander populations in Oregon.

The Various Legacies of AAPI Communities in Oregon

There is a long and interwoven history of Asian and Pacific Islander (AAPI) people in Oregon and many organizations focused on preserving the cultures and telling the stories of these communities here. The Japanese American Museum of Oregon (JAMO) in Portland, recently re-named and relocated to the Naito Center, is one such organization. In recent news, the National Trust for Historic Preservation awarded $25,000 to JAMO and the Architectural Heritage Center to help fund a collaborative project chronicling the history of Japanese Americans in Portland during the 20th century.

However, the U.S. has not always honored AAPI cultures, and for a while, the state of Oregon tried to exclude members of AAPI communities from settling here altogether. The 1850 Donation Land Act specifically forbade Chinese and Pacific Islander people, along with other nonwhite residents, from owning land in Oregon. Since then, there has been a long history of discrimination against Chinese Americans in Oregon.

The exclusion of Pacific Islander people became apparent during the 19th Century when they played a prominent role in the Oregon fur industry. White American men in the fur industry felt threatened by Pacific Islander workers’ ties to the Hudson’s Bay Company, heart of the British fur trading business. Despite the exclusionary measures taken against Pacific Islander people in the past, there are many Pacific Islander organizations across Oregon today that specifically serve this population. The Compact of Free Association Alliance National Network is one that works to provide social and economic justice to COFA communities in the state of Oregon.

In the 20th Century, the Oregon legislature targeted Japanese Oregonians because they were seen as a national threat. There is a well-documented history of Japanese-American internment in Oregon during WWII. Over 4,000 Portlanders of Japanese ancestry were forcibly relocated to internment camps for the duration of the war. In May of 1942 they were sent to temporary detention camps, and by the summer of that year, the War Relocation Authority sent them to permanent “relocation centers,” where they suffered inhumane living conditions for years. On January 2, 1945, the War Department declared that the Japanese were free to leave camps, but their return to Oregon was slow due to widespread anti-Japanese sentiment.

After WWII, some of the Japanese Americans who were forced to live in internment camps moved to Vanport, Oregon, enduring even more upheaval and displacement — like the Black and Indigenous communities that inhabited this housing project as well– after the Vanport Flood hit in 1948. June of 2022 marks the 80th anniversary of Vanport’s construction and the 7th annual Vanport Mosaic Festival, taking place from May 20 – June 7. Check out our May 2021 newsletter for more information about it. This year’s festival features arts performances, screenings, exhibits, tours, dialogues, gatherings, and celebrations that highlight the cultural mosaic that Vanport represented.

During the Vietnam War, the Hmong people in Laos provided intelligence, monitored Communist forces, and helped to rescue downed American airmen to support U.S. forces in the 1960s. As the Vietnam War came to an end in the 1970s, displaced refugees from South Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos flocked to Portland. In 1975, when the war ended, thousands of Hmong families fled to refugee camps in Thailand and were resettled in the U.S. Oregon was one of the largest Hmong resettlement locations, with a population of 4,500 Hmong people by 1981. As a result of displacement caused by the Vietnam War, people of Vietnamese origin now make up two percent of the Portland population and an estimated 330,000 people of Hmong origin reside in the U.S. as of the 2020 census.

In 1976, a group of Vietnamese, Laotian and Cambodian refugees formed the Indochinese Cultural and Service Center (ICSC) with the purpose of helping newly arrived families adjust to life in the U.S. In the 1980s, ICSC joined another community organization, the Southeast Asian Refugee Federation, to form the International Refugee Center of Oregon (IRCO). In 1994, IRCO founded the Pacific Islander and Asian Family Center to provide culturally specific services to Asian and Pacific Islander immigrants and refugees in Portland. Renamed as the Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization in 2001, IRCO helped the growing populations of Southeast Asian immigrants and refugees to adjust to American culture and find jobs.

Modern Day AAPI Experiences and Influences in Oregon

Portland’s Jade District illustrates the cultural influences of different AAPI communities on the city today. One of Portland’s — and Oregon’s — most diverse neighborhoods, the Jade District is largely home to a population of immigrants and people of color who speak an array of languages. Known for its gastronomical offerings, its varied styles of restaurants and grocery stores reflect the cultural diversity of the Jade District’s communities.

In 2011, the City of Portland chose the Jade District as one of eight Neighborhood Prosperity Initiative districts. The program has since been adopted by the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon (APANO). According to its website, it is a place-based, community building and economic development program of APANO’s Communities United Fund focused on improving the ten-block radius surrounding Southeast 82nd Ave and Southeast Division Street.

Over the past few years, Asian Americans and Pacific Islander people have faced increased discrimination related to the COVID-19 pandemic based solely on their perceived identities. Members of these communities have experienced an increase in hate crimes and threats of violence, which studies show has negatively impacted the overall mental health of these populations.

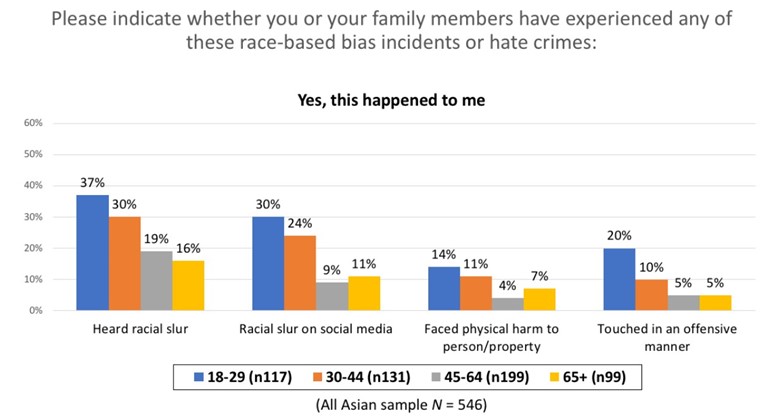

In 2020, reports of hate crimes and bias incidents increased by 366% in Oregon, with 20% of the reports in April of that year coming from members of the AAPI populations. Based on statewide surveys proposed by Portland’s Asian Health and Service Center and APANO and conducted by the Oregon Values and Belief Center between 2021 and 2022, out of a population of approximately 74,400 Asian Oregonians, nearly 50 percent of respondents reported having a racial slur used against them or a family member.

Oftentimes, members of different Asian and Pacific Islander ethnic groups are seen as homogenous and interchangeable to people outside of these communities. However, each of these populations has an individual culture separate from other AAPI identities, with different languages, histories, struggles, strengths, and traditions unique to each one.

Learn More About AAPI Cultures

Here are some resources where you can learn about the individual communities that make up the Asian and Pacific Islander populations in Oregon:

- APANO – Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon

- Portland Taiko – Affirm. Inspire. Create./ Portland Taiko (oregonencyclopedia.org)

- Portland Japanese Garden

- The Compact of Free Association Alliance National Network

- Check out the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education’s Oregon Rises Above Hate event on May 14. Join in-person or via livestream to celebrate these communities, their resilience, and commit to combat the continued rise in anti-Asian hate.

- As part of Oregon Rises Above Hate, OJMCHE admission is free on Saturday, May 14, 11am-4pm. The following cultural organizations will also be offering free admission on this day in addition to OJMCHE.