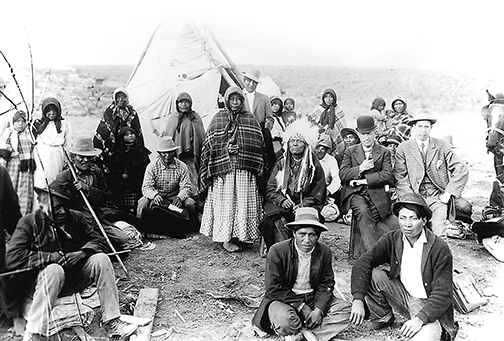

Image from Oregon is Indian Country exhibit on display Dec. 1, 2022 – Jan. 31, 2023, at the Independence Heritage Museum (Source: ohs.org)

During October, the state of Oregon recognizes Indigenous Peoples’ Day on the second Monday of the month. Although the holiday was first proposed by Indigenous peoples at a United Nations conference held in 1977 to address discrimination against Indigenous peoples in the Americas, it was only first recognized nationally by the Biden Administration on Oct. 11, 2021. However, it is still not considered a federal holiday.

The State of Oregon first recognized Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a state holiday in 2021. This law was set in motion by Oregon’s only Indigenous lawmakers, Rep. Tawna Sanchez, D-Portland, and Rep. Teresa Alonso-Leon, D-Woodburn, who brought House Bill 2526 to the Oregon legislature in the spring of 2021. This blog post will cover the history of Indigenous peoples in Oregon and modern-day issues Indigenous communities face.

A History of Reservations, Termination and Restoration

As a result of the whitewashing of the history of Native genocide, much of Indigenous history has been erased by settler-colonial narratives in Oregon. Senate Bill 13 called upon the Oregon Department of Education to develop a statewide curriculum relating to the Native American experience in Oregon. Enacted in 2017, it includes tribal history, tribal sovereignty, culture, treaty rights, government, socioeconomic experiences, and current events. The following is a summary of the history of governmental control of Native lands, abuse, and genocide of Indigenous populations throughout Oregon’s history.

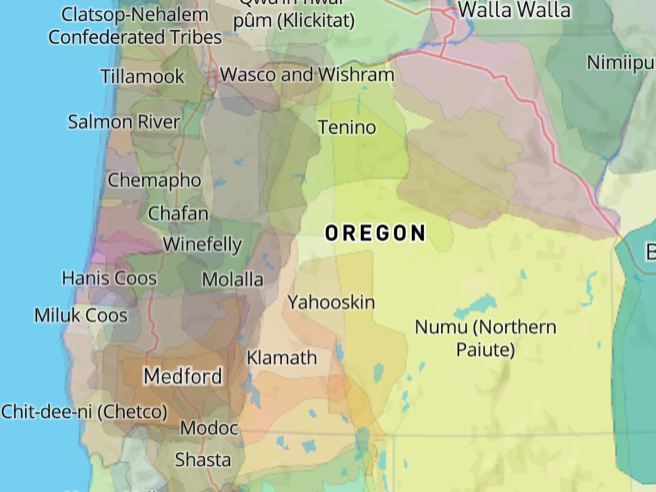

Indigenous tribes have existed in Oregon since time immemorial, and Native populations have long stewarded the land that the U.S. has colonized. After suffering decades of diseases brought by European settlers, like malaria, and genocide inflicted by European colonizers, many Native populations in Oregon were decimated. It is estimated that by 1850, the population of the Kalapuya, one Native tribe who originally occupied over a million acres across the Willamette and Umpqua Valleys, went from over 20,000 people to about 1,000. Use this interactive map to find out what Native land you live on.

The Reservation Era (1850-1887) in the U.S. came after the disinvestment and removal of Native peoples from their homelands, enforced through violence and terror. During this era, dedicated portions of land were allocated to federally recognized tribes. In Oregon, the federal government intended the Coast Indian Reservation to be the sole permanent reservation in western Oregon for the native peoples of the Willamette Valley, southwestern Oregon, and the coast.

The principal tribes who signed the treaties to negotiate the cessation of their lands in exchange for the dedicated reservation were the Umpqua, Athapaska, Kalapuya, Molala, Chasta, and Chinook. After the Rogue River Indian war broke out in the spring of 1855, President Franklin Pierce signed the executive order establishing the Coast Reservation that fall.

In 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant established the 1.8 million-acre Malheur Indian Reservation for tribes living in eastern and southeastern Oregon. The intent behind the U.S. government negotiating treaties with Native peoples was to lump different tribes together to gain control over their lands and resources. Use this interactive map to see a time-lapse of how the U.S. stole more than 1.5 billion acres from Native Americans.

This practice led to the government consolidating formerly independent tribal nations onto reservations often far from their homelands. One example is the Grand Ronde Reservation, to which members of 27 tribes and bands from western Oregon, southern Washington, and northern California were removed.

By the 1950s, the U.S. government began enacting legislation to terminate trust relations with Native tribes and the 374 United States-Indian treaties that were ratified between 1778 and 1871. With the goal of giving opportunist constituents the ability to capitalize on natural resources located on reservations, the federal government targeted tribes like the Klamath and the Menominee for their rich timberlands. To eliminate Native sovereignty over their lands, the 83rd Congress passed Public Law 280 in August of 1953, which allowed Oregon and five other states to have civil and criminal jurisdiction over reservations.

Congress also approved House Concurrent Resolution 108 in August of 1953, which directed the government to make the Native peoples within the territorial limits of the U.S. subject to the same laws and entitled to the same privileges and responsibilities as other American citizens, effectively ending their status as wards of the U.S. However, tribal citizens were not granted the right to vote until 1953. This action not only undermined tribal sovereignty, but also cut off treaty-guaranteed services, and took even more land out of Indigenous hands.

Despite their agreement to these treaties, many Native people, like the Klamath, felt misinformed and misled by the termination treaties they agreed to, with legal consequences of certain sections of termination laws leading to unequal outcomes. For example, Klamath lands had been appraised for $91 million, resulting in 1,659 individual members of the tribe receiving a one-time payment of $44,000. With 590,000 acres of rich timberland in the balance, the payoff for opportunists in the timber industry was much greater than it was for the tribal members.

In 1975, Congress considered the Siletz Restoration Act, backed by Oregon Senator Mark O. Hatfield. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, tribal members from different tribes lobbied and testified to regain recognition and restore their terminated federal trust relationships. Recognition was restored thanks to decades of tireless work by tribal activists. Since then, restored tribes in Oregon have been working to rebuild their nations over time. As of 2022, there are 574 federally recognized tribes, approximately 229 of them in Alaska. There are many federally unrecognized tribes as well.

Modern Day Indigenous Communities

Today there are nine federally recognized tribal communities in Oregon. They consist of the Burns Paiute Tribe, the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, the Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians, the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon, the Confederated Tribes of the Siletz Indians, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, the Coquille Indian Tribe, the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians, and the Klamath Tribes.

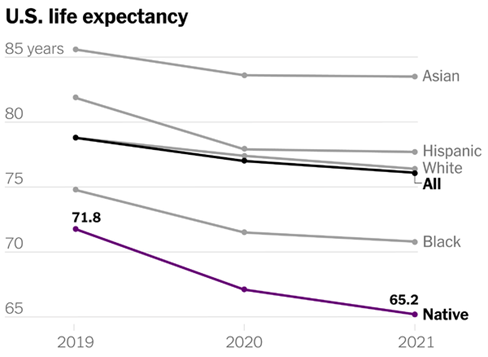

Over the past few years, COVID-19 has caused a massive death toll in Indigenous communities. Between 2019 and 2021, the average life expectancy of Native Americans dropped by almost seven years. Experts link this sudden drop in life expectancy to higher rates of poverty within Native communities, with more underlying health problems, like obesity and diabetes, which exacerbate COVID-19, as well as the overall lack of access to healthcare.

Due to a lack of resources, unrecognized Indigenous tribes in particular are struggling greatly with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their communities. While federally recognized tribes received billions of dollars in COVID-19 relief funds, unrecognized tribes have been left empty-handed.

Despite the challenges that Indigenous communities are facing, there have also been many triumphs due to Indigenous movements in recent years. Led by Indigenous communities, the landback movement has helped influence environmental successes like the imminent removal of the Klamath River dams located on the border of California and Oregon. The hydroelectric dams, owned by the electric power company, PacifiCorp, are set to be removed in 2024.

After a 20-year fight to save the chinook salmon, the long sought-after removal of the dams will open 420 miles of salmon-spawning habitat, improve water quality, and reduce critical temperature conditions that cause and increase disease in fish. The self-governed Karuk Tribe, Yurok Tribe, and the U.S. Forest Service are all closely monitoring the salmon population along with other agencies.

Founded in 1993 by the late Martin High Bear, Lakota medicine man and spiritual leader, and Rose High Bear, Deg Hitan Dine (or Alaskan Athabascan), and Inupiat, Wisdom of the Elders Inc. is an organization based in Portland that works to promote Native American cultural sustainability, multimedia education, and cultural reconciliation. They host regular public cultural events throughout Oregon and offer paid internship opportunities for Native American adults and BIPOC in the Portland area.

Housing News in Indigenous Communities

In May of 2022, the U.S. Department of the Interior released a 100-page report on federal Indigenous boarding schools of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, detailing the abuse of students and over 500 student deaths. While the report offers valuable information about the history of government-backed abuse of Native populations in the U.S., Deb Haaland, Interior Secretary and first Native American cabinet secretary responded by pointing out that the continued disparities that Indigenous communities face today are examples of the ongoing attempts to forcibly assimilate Indigenous people. You can read more about the sordid history of Indigenous boarding schools in our November 2021 Bus Tour Newsletter.

The Native American Youth and Family Center (NAYA) in Portland is one organization addressing the unique needs of Native populations in the region. They provide housing along with culturally specific services with the goal to empower Native people. They recently opened the Mamook Tokatee housing project in the Cully neighborhood in Northeast Portland.

Named for the Chinook Wawa phrase meaning “Make Beautiful,” the project is a collaboration between the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians and Community Development Partners. With 56 total units, 20 units are reserved for members of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians and six units are meant specifically for artists.

Learn More About Indigenous Peoples in Oregon:

The indigenous peoples of Oregon have a long history worthy of celebration, commemoration, and reflection. However, it is equally important to recognize the contributions of the living culture of today’s Native American communities. Here are some resources where you can further explore the past, present, and future of Indigenous culture:

- The Oregon Encyclopedia – Indigenous Peoples’ Day

- The Museum At Warm Springs – Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs (warmsprings-nsn.gov)

- Chachalu Museum and Cultural Center | Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

- TAMÁSTSLIKT CULTURAL INSTITUTE | Immerse yourself in history (tamastslikt.org)

- Two Hundred Years of Changes to Native Peoples of Western Oregon (ohs.org)

- Oregon Experience | Broken Treaties, An Oregon Experience | Season 11 | Episode 1103 | PBS

- About Confluence – Confluence Project

- Chinook Indian Nation | Chinook Tribe – Cathlamet | Clatsop | Lower Chinook | Wahkiakum | Willapa (chinooknation.org)

- Home | Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

- History – Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs (warmsprings-nsn.gov)

- Native Gathering Garden at Cully Park | Portland.gov

- Native Arts and Cultures Foundation